Showing posts with label Western Civilization. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Western Civilization. Show all posts

2015/05/01

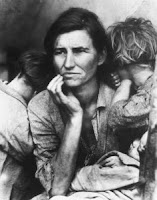

Introduction to This Month’s Topic: The History of Women in Western Civilization

This was a class I wanted to take for a few reasons. One reason is that I love history and it feels like I have studied it all my life. I grew up with a thirst for it and devoured every book I could find that I could understand. I think that this passion for learning and history has served me well in my life and has been very enjoyable for me. However, I found that I felt over time that my knowledge was really very limited and as I looked at it from an education and a religious standpoint, I realized that I pretty much can give the basics on many of the individuals that have made history, but the majority are men. The exceptions in my mind can be classified as wealthy, white, powerful women such as Catherine the Great of Russia and Queen Elizabeth I of England... which were rare. Over the last year or so, I have tried to change that and have actively tried to look at the flip side of the coin so to speak. I have found the information a lot more challenging to come by and having anyone to discuss the information I do find with is difficult because the history of anyone besides men isn't taught in most standard classes so the discussion becomes a bit of a lecture or monologue.... which is no fun at all. So I saw this particular class as a lot of fun and a great resource towards gaining more knowledge, but also more guidance towards more resources for future study. I was hopeful that I can learn more not only about women and their struggles in culture, families and in creating a human history of their own, but also that I can develop a better understanding of the struggle for gender equality that is going on in my own lifetime. I also wanted to have a better understanding of how power and entitlement work between gender, class and race and how people are working towards changing the cultural biases that affect the under-privileged majority of people.

I found myself really interested in learning about how women's history is being compiled by historians and feminists today and how, as history is complied, what forces or parts of culture tend to decide which history is most important for the average student to learn about. I recognize that politics enters that equation as well so I understand that question must needs be open ended without a full solution to be had.

I think that anyone who approaches any of this information differently on a few levels. As our gender is intertwined in our mind and our thoughts without it being consciously there, each individual will have no choice but to either ignore or recognize that you will look at in the material based on your gender. However, I think that we are each much more likely to approach the material from a just as personal and unapproachable bias.... the bias of our own life experiences as well as current life circumstances. Our experiences, culture, family and our choices over time have helped each of us develop into a unique and amazing person and we cannot help but approach any topic with those biases in place and work to try and set them aside as we study and try to look at the topics addressed. I do not think that it is possible for any of us to do that completely- part of me at least has a hard time recognizing biases in myself and I assume others may have the same difficulty in self reflection and introspection. So I suspect that even when many of us appear to see the topic in the same 'light' and have the same viewpoint, we are getting there from very different paths and thoughts.

I recognize that the topics that I will address in the next several posts may be unknown to most and may also be on topics that are sensitive or cause negative emotions in yourself and others. I am not sharing them to cause any harm or anger; rather, I am sharing because I believe that the only way to change culture is to talk about it. From my writings, you will find that some of these topics were challenging for me and my emotions will hang off of some of my sentences and paragraphs. I hope that as readers, we can share our thoughts freely and discuss our feelings and concerns on the history and the topics that are discussed… many of which are still relevant to ourselves and women around the world today.

pictures from: http://www.citelighter.com/film-media/fashion/knowledgecards/womens-fashions-of-the-medieval-era, https://oregonheritage.wordpress.com/2012/05/18/oregon-womens-history-project/, https://oregonheritage.wordpress.com/2012/05/18/oregon-womens-history-project/, http://www.ora.tv/offthegrid/article/grid-history-women-history

Labels:

bias,

Catherine the Great (Russia),

culture,

daily life,

Elizabeth I (of England),

experience,

gender,

history,

introspection,

knowledge,

power struggles,

Race,

religion,

self reflection,

Western Civilization,

women

2014/03/22

Did the Russian State... Part XIV by Nils Johann (Conclusion)

It are not always the material ripples of historical events that reach us. The stories of events that in their time were relevant, may much sooner reach us. The way these then are imbued with new meaning, sometimes is the only thing that makes a historical event seem relevant. It is in some way misleading, to maintain that past occasions, at any price, effect future development, that is far-flung in time, and separated by centuries. The second chapter of the paper demonstrated this, all though from an 'eagle's perspective'. This enabled us to see how the myth of a liberal, democratic and prosperous 'Western Europe', by force or ignorance, has been projected back in time, to comply with our contemporary notions and fancies of what is right and proper, while disregarding the immense change, forced upon the societies, and Institutions, that experienced the brunt, and sudden force of the Industrial Revolution.

On that basis it seems plausible, that the backwards-projection of Cold War reality, like in the leading case of Wittfogel's Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study in Total Power, certain misleads, and errors, have been allowed to occur in our perception of 16th century Russia. A tense Anglo-Russian relationship during the middle of the 19th century may have worked to establish the same effect, during the infancy of modern historiography. The emphasis on what separates the Russian and 'West-European' state formation process of the 16th century, is therefore in this paper interpreted as a false dichotomy. The dilettante 'National Histories' of the age, that favored long chains of causality for explaining their contemporary surroundings in the frame of 'The Nation', assumed, just like Yanov, Landes, Ferguson, and others, that there must be a chain-reaction spanning centuries in order to explain their contemporary condition. In order to make the writing more relevant lines of connections seem to be forced into the narrative, either backwards or forwards. Cum hoc ergo propter hoc, is a common error of reasoning where 'Correlation' is mistaken for 'Causation'. We need not all act as Skinner's pigeons.

This paper notes the challenge posed by the anachronistic concepts superimposed on the interpretation of the age, to understanding the age of Ivan and Henry on its own premise. As a response it attempts a comparison of the reigns of Ivan IV and Henry VIII. The comparison is intended to serve as an internal frame for reference for the period, but is also a search for positive similarities between the regimes. What is shown by this is a general similarity. It is tricky in such a comparison to discriminate perfectly without going in the trap of just 'cherry-picking' the examples one wants, but the paper focuses on the general conditions of statecraft of the age. By giving a general introduction to wider European developments, shaped by stronger Monarchs, who manage a paper-bureaucracy, and standing gunpowder armies, the paper sets the stage of its main subject, while establishing possibility for wider contextualisation. It then progresses to an introduction of the formation of the 'royal houses' of Henry VIII and Ivan IV, with a brief resume of their families 'road', to the power that the Monarchs would wield. Both monarchs temper and subdue the noblemen that surround them in order to ferment their own power-base. Their methods were brutal and efficient. Whether the opponents of the Crown were executed by boiling alive, drawn and quartered, or any other number of imaginative methods, the principle seems to be the same with both Crowns: Maintaining order by demonstrating power, through the application of violence.

Simply: Installing Terror. The Technical breakthroughs of the time enabled the ruling of larger territories, accompanied by centralization of power, not seen in Europe since the decline of the Roman Empire. This then also called for a restructuring of governance. Parliamentary systems are reformed to adapt to this reality and, are re-functioned to act as management organs of the Crown. At the time none of these Parliaments are embryonic 'democratic' institutions, in the modern sense of the word, but they function as a line of communication between the Monarch and the Commoners. Their main function is however to recognize the laws of the Monarch, and to effectuate the levying of taxes. The taxes are in both cases intended to serve the foreign policy of the King. - The protection of the realm; the execution of war-craft. Differences occur in the detail of how Ivan and Henry chose, or can choose, to fill their 'war-chest', and there is better method to the plan of Henry. He implicates part of his loyal nobility in his robbery of the Church, while Ivan's Oprichina leads to the estrangement, and tempering, of his high nobility. The funds from their respective heist, do however go towards the same purpose. They carry the war to their enemies, subduing them, plundering, and gaining dominance of even larger tracts of land. By the crack of the lash, and the screaming of cannon, with bloody sword in one hand, and a pen in the other, surrounded by rich palaces and poor peasants, gibbets, and henchmen, proto-bureaucratic states were formed, both in England and in Russia. They were materializing in all of Europe in the period.

Comparing two reigns of respectively forty-three and sixty years, of almost continual warfare at the western rim of Eurasia, called for an eagle-perspective in this paper, that ignores detailed differences in the formation of Russia and England, which there of course are. The grand lines of the narrative of the paper, however demonstrates that there are remarkable similarities in the formation of Russia and England. Russia is in its proto-state's functioning, during the period of the 16th century, more alike, than unlike England.

So, if you have taken the time to read through this whole paper, what are your thoughts? Any disagreements? What did you like and feel like you learned?

2014/03/12

Did the Russian State... Part V by Nils Johann (Why, and how to compare the Rule of Henry VIII with the Rule of Ivan IV?)

Maybe the best way to clear the question, of the comparability of the formation period of the Russian State, is by comparing more or less contemporary case. Noam Chomsky formulates this approach in several of his publications but the most elegant formulation stems from“Manufacturing Consent”(1992):

“Interviewer: I'd like to ask you a question, essentially about the methodology in studying 'The Propaganda Model' and how one would go about doing that?

Chomsky: Well, there are a number of ways to proceed. One obvious way is to try to find more or less paired examples. History doesn't offer true, controlled experiments but it often comes pretty close. So one can find atrocities, or abuses of one sort that on the one hand are committed by "official enemies", and on the other hand are committed by friends and allies or by the favored state itself (by the United States in the U.S. case). And the question is whether the media accept the government framework or whether they use the same agenda, the same set of questions, the same criteria for dealing with the two cases as any honest outside observer would do.”

As long as 'The Cold War' lasted, it may have seemed like there was a definite line separating “Eastern” and “Western” culture. The global political power-struggle that took place, did, or at least it seems to have, overemphasized difference. Most likely this dominantly happened as a conscious relation towards the conflict by the authors, and to a lesser degree because of the restricted opportunities to communicate and cooperate across the political divide that was formed by 'The Cold War'. It was primarily a power-political divide, but not necessarily a clear cultural divide. To most conflicts between any given parties, a certain animosity will follow. It becomes easier to dehumanize the enemy, and this is done by starting out, to look for differences, not for

commonalities. Dichotomies that support this attitude of animosity have to be found out and cultivated. When these differences are cultivated and (over)exaggerated, they will after time be held to be basic truths, and misinterpretations will happen.

Surely the period we are going to discuss; Russia, roughly from the 15th to the 17th century, is somewhat removed from the issues of the 'Cold War'. But the 'Cold War ideology' may have been lurking in the background, in the consciousness of the historians interpreting. Even if there is an honest appreciation for historical facts internalized in the scholar, this is not in itself a guarantee for an accurate assessment of the past. At least not in the environment of contagious anti-communism, before, during, and after the time of the Soviet Union.

This paper is not the first attempt at comparison. Edward Keenan already deemed it futile back in the 70's, to find any means of aligning Russian history, with its “European” contemporary counterpart. But for those who have seen his works, it becomes clear how concerned he was with “detail”. In Keenan's world there was not much room for comparing anything. Michael Cherniavsky, Halperin's mentor, however inspires an attempt at comparison, portraying the traits that make Ivan a proper “renaissance prince”. There are many traits that offer themselves as similarities.

There is no question that Russia is different from Britain during the 16th century, just like every other institution is different from the next. The biggest difference between the two units might be the size and the geographical attributes they contain. In the time, transport by boat was far more efficient than overland travel, giving a comparative logistical advantages to the English. They are surrounded by the sea, whilst the Muscovites were depending on their river-systems, to connect an area that in average was far less densely populated than England, and at least, ten times more expansive. Further difference is that far more sources have survived in England. Wooden Moscow was 'put to the torch' several times by various enemies. In addition England got its first printing press in 1476, while the first Muscovite press was set up in 1553. English sources are also more widely accessible to western scholars, than sources written in Russian variations.

Arguing for a Sonderfall still might not be the most fruitful thing one can do, even though, I must admit it could be done in any case, regarding any institution. -The refusal of the abstract concept of the forest, in favor of our favorite tree. The Crowns of both Henry and Ivan, handle their opponents and the nobility harshly, they constantly make war and their finances suffer. The way their respective parliaments function seems kindred. Behaving like prototypical Autocrats, both are good examples of the ruling-style of their period, being held up as the best form of government in Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil (1651) about a hundred years later.

Labels:

absolute monarchy,

autocrat,

Cold War,

communism,

dehumanize,

England,

Great Britain,

Henry VIII of England,

Muscovite,

Nils Johann,

Noam Chomski,

politics,

propaganda,

Russia,

Soviet Union,

Western Civilization

2014/03/10

Did the Russian State... Part III by Nils Johann (The Myth of 'Oriental Despotism')

“...nor is it good to have many rulers. Let there be one ruler, one king,...”

We tend to look at the Eurasian landmass and then we single out about a 5% of it. We say; this is freedom, enterprise, 'development', in complete opposition to the other 95%, ruled by Oriental Despotism. That these other nineteen twentieth, should be no more or less special, or equal, in their 'strangeness' seems to be rather more likely. But this is not what is usually seen, when we talk of this mythical difference, between two more or less incomparable units. It is not amazing when travelers in the 16th century find new places to be strange, but this does not make these places more strange for us looking back through more than four-hundred years of passed time. The Work of Goldstone, like Frank's, points in the direction that there might be serious errors in how 'The West' and 'The Rest' are presented. These errors skew our understanding of our history in general. He suggests an alternative interpretation:

“The California school reverses this emphasis and sees Europe as a peripheral, conflict-ridden, and low-innovation society in world history until relatively late. Superiority in living standards, science and mathematics, transportation, agriculture, weaponry, and complex production for trade and export, has multiple centres in Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley and the Yellow River Basin. From these regions civilization spreads outward,...while western Europe remains a primitive backwater. When civilization spreads West with Carthage and the Roman Empire, it remains rooted in the Mediterranean and then—with Byzantium—in Anatolia.” “Except that something goes haywire in England. Charles II dies without an Anglican heir, and the throne passes to his Catholic brother James.”

We should not interpret this as a straight forward dissemination theory because that would be unoriginal, but as a more complex gradual transplantation, or adoption, of tools and technique for government. This then fits rather well with Gerhard Spittler's explanation of 'despotism' and how it has worked. And Spittler's 'despotism' is not the mythical 'totalitarian', 'oriental despotism'

-understanding of the word of Wittfogel and Ferguson.

How 'despotic' is 'The East' really in comparison to 'The West'? The question is interesting because Spittler diagnoses 'despotism' to be the management-form of primitive state-structures. 'Despotism' is described as a rule over farmers with a military-state, that has little developed bureaucratic structures, or codex laws. - as an opposite of 'bureaucratic government'. Spittler, however, found that Prussia of the 18th century, and West-Africa of the 19th century compare rather well in this regard.

“The peasantry in a peasant state is characterized by a great diversity of local customs and by defensive strategies. Both are related to peasants' semi-autark household production. Under these conditions the central government lacks information and the means of control. Administration by intermediaries and despotism becomes widespread because it is well adapted to this situation. In order not to be infected by the “chaotic diversity” in the countryside, the bureaucracy maintains its distance from the peasants. But on the other hand, it also tries to penetrate the peasantry. Bureaucratic administration requires the collection and storing of information, so a precise census is a basic tool for bureaucratic work.”

As an extension of this, we can assume that almost every state, until the development of industrial society, were peasant states, trade being, in general, marginal. The road away from despotism, to a more bureaucratic state, with more order, less random violence or ad-hoc power, is similar. This would in turn mean a tempering of the aristocracy and the centralization of power to the Crown, as it again, from the period after 1450, increasingly happened in all of Europe. Mind, not as a straight progression, and not at all always successful.

The portrayal of the “oriental despotism” therefore seems methodologically unsound. The theoretical separation of 'The East' and 'Western Europe' seems to be creating some confusion when it comes to understanding the workings of reality, rather than being helpful in this regard, as a theory should be. To help us along it might be helpful to summarize some scientific theorems. A false dichotomy arises, when the premise for the given research proposes that there are only two possible outcomes that are mutually exclusive. With the induction of such a premise, we run the risk that maybe both outcomes are wrong, or that they are not mutually exclusive. The danger for research-work, premised by a false dichotomy, is that it may lead into a falsity in logical reasoning. The result could be misguiding, leading us to make wrong conclusions. The false dichotomy is therefore also a common rhetorical technique, where only two choices exist, only two real alternatives. A false dichotomy can just as well be an intended fallacy, created in order to force a decision where none of the alternatives, are necessarily the correct choice.

The western rim of Eurasia is more similar in its development up until about 1800 than might seem palatable. Splitting Russia off from the state-formative processes taking place in other locations alongside 'The Rim' therefore does not serve the purpose of gaining understanding, but causes alienation. The terminology in use for later periods still puts the “dictatorship” of the USSR next to its 'imagined-free', NATO opponent, in an imaginative exercise of a combination of hypocrisy, avarice, and ignorance, that trumps any nuance. In the same manner the brutal occidental Barons of late medieval Europe are painted to be 'Arthuresqe' figures of myth next to the bloodthirsty oriental Despot.

Comments? Questions...? :)

2014/03/08

Did The Russian State Form in a Different Manner than Its Occidental Neighbours? - Part I by Nils Johann

Can Russia be seen as following the same formative patterns as the new bureaucratic (proto-) states rising in Western Europe? A discussion in historiography, world history and the problems of long chains of causality, exemplified by a comparison of Russian and English political history during the reigns of Ivan IV and Henry VIII. (Late medieval/Northern Renaissance period, 16th century.)

While studying medieval Russia two questions kept popping up in the Literature: Does Russia have its background in “Eastern” (Asiatic) or “Western” (European) culture? Does a possible Asiatic background account for the perceived “backwardness” of the land? During the reading, a suspicion of double-standards for the 'scales' we use to measure the 'East' and the 'West' arose. Marginal cosmetic differences seemed to be exploited to exasperate a narrative, of a distant, strange, and mythical Russia. The historiographical discussion will start with the more specific grand works and perspectives concerning Russia, opened up by Ostrowski's essay on "The Mongol Origins of Muscovite Political institutions", which served as a inspiration for this work. What then also needs to be addressed is the claim of Russian backwardness which is the main narrative thread in Alexander Yanov's work, and in large parts in other writings, like the work of Wittfogel. Is the way Russia is portrayed up to this day, intentionally overemphasising minor differences, as a result of the political tension that ensued between its rulers and the neighbors in 'The West', rather than a matter of fact? Could the portrayal also be the result of sloppy methodology... even if some Russian scholars themselves adopt this view during the zenith of British hegemony, in the middle of the 19th century? It became my desire to look at the subject with a 'Homeric blindness' and a 'Ranke'an' moral disassociation.

While dealing with this question the main challenge gave itself by the seemingly ethereal qualities of terms like 'Europe' utilized in the discussion. An approach was finally opened up by 'zooming out' and taking a look at Frank's work in "ReOrient- Global Economy in the Asian Age" (1998) and by the discussion that ensued between him and Landes, Goldstone, Vries, Pomeranz and others. I still remember discussing the 'hot topic' of the 'special' European development with Vries back in 2004, and also that it ended with Vries passionately leaving.

I will make an account of this larger discussion further on because it will provide the proper context for discussing what 'Western Traits' actually are, and how far back we actually are honestly able to superimpose this term back in time. Goldstone's suggestion: To see Europe as the (*'barbaric') rim-lands of “Civilization”. Civilization at first spreading from Mesopotamia, in the direction of Europe, is a good perspective for helping us understand this.

With the narrative, that: Every time non-European state-formations have stability, their government can inherently, within this discussion, be described as despotic or tyrannical, we might be led astray: As long as there was order in China, and India, up until about 1800, these areas also maintained a technical lead on poor, war-torn Western-Europe: Stability equals innovation, because relative risk is reduced, and more persons are allowed to specialize. Risk becomes acceptable when it is affordable to take a loss.

In order to answer the question of the paper, what follows is an introduction to the greater European realm during the lives of Henry VIII (*1491-†1547) of England and Ivan IV (*1530-†1584) of Russia. This context is important, because looking at Russia isolated, can sometimes make us forget the realities of late-medieval/Renaissance life, in its westward neighbors. We could go into the trap of unintentionally only comparing it to our life experiences today, leading us to handle the subject-matter unhistorical. The demonstration will then continue by looking at, and comparing their reigns, which are more alike, than proponents of British exceptionalism, or of the Asiatic culture of Russia, would care for. We start out by comparing their families rise to power and their relation to the other noble families. There follows a comparison of their household management, the legal status of the Emperors, and their warfare.

In several works by, amongst others, Crummy and Yanov, the reign of Ivan IV is held up as an example of 'non-European' political behavior. When we with that approach compare Ivan's reign to that of Henry VIII, interesting choices for conclusion open up. Neither Henry, nor Ivan, are behaving like the Europeans of Ferguson or Wittfogel. The alleged “democratic”, free Occident, stands like an elegant myth, with its cradle in a later age. In short, the privilege of a few noblemen in Britain after 1688, does not make out as credible freedom, and in the 1540's, English political conditions do not stray remarkably from conditions in Russia. In the comparison of chapter 4, a pattern will emerge, that highlights the similarities in behavior of the two Monarchs and their Crown. Both castigate and subjugate the other competing nobles. In order to accumulate capital they reform their management and communication systems, laying the groundwork for a bureaucratic state. They do this in order to exploit the realm, and to aggregate power in their own hands. This enables their wars of conquest. Standing gunpowder-armies enable them to project their power further than their predecessors. It should be acknowledged that differences between England and Russia, but when looking at the grand motions, an impression of similar development for the period forms.

Comments.... Questions? :)

Labels:

absolute monarchy,

China,

culture,

Europe,

Henry V of England,

India,

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (the Terrible),

medieval history,

Mesopotamia,

Mongol,

Muscovite,

Nils Johann,

Renaissance,

Russia,

war,

Western Civilization

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)