Showing posts with label Henry VIII of England. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Henry VIII of England. Show all posts

2014/03/22

Did the Russian State... Part XIV by Nils Johann (Conclusion)

It are not always the material ripples of historical events that reach us. The stories of events that in their time were relevant, may much sooner reach us. The way these then are imbued with new meaning, sometimes is the only thing that makes a historical event seem relevant. It is in some way misleading, to maintain that past occasions, at any price, effect future development, that is far-flung in time, and separated by centuries. The second chapter of the paper demonstrated this, all though from an 'eagle's perspective'. This enabled us to see how the myth of a liberal, democratic and prosperous 'Western Europe', by force or ignorance, has been projected back in time, to comply with our contemporary notions and fancies of what is right and proper, while disregarding the immense change, forced upon the societies, and Institutions, that experienced the brunt, and sudden force of the Industrial Revolution.

On that basis it seems plausible, that the backwards-projection of Cold War reality, like in the leading case of Wittfogel's Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study in Total Power, certain misleads, and errors, have been allowed to occur in our perception of 16th century Russia. A tense Anglo-Russian relationship during the middle of the 19th century may have worked to establish the same effect, during the infancy of modern historiography. The emphasis on what separates the Russian and 'West-European' state formation process of the 16th century, is therefore in this paper interpreted as a false dichotomy. The dilettante 'National Histories' of the age, that favored long chains of causality for explaining their contemporary surroundings in the frame of 'The Nation', assumed, just like Yanov, Landes, Ferguson, and others, that there must be a chain-reaction spanning centuries in order to explain their contemporary condition. In order to make the writing more relevant lines of connections seem to be forced into the narrative, either backwards or forwards. Cum hoc ergo propter hoc, is a common error of reasoning where 'Correlation' is mistaken for 'Causation'. We need not all act as Skinner's pigeons.

This paper notes the challenge posed by the anachronistic concepts superimposed on the interpretation of the age, to understanding the age of Ivan and Henry on its own premise. As a response it attempts a comparison of the reigns of Ivan IV and Henry VIII. The comparison is intended to serve as an internal frame for reference for the period, but is also a search for positive similarities between the regimes. What is shown by this is a general similarity. It is tricky in such a comparison to discriminate perfectly without going in the trap of just 'cherry-picking' the examples one wants, but the paper focuses on the general conditions of statecraft of the age. By giving a general introduction to wider European developments, shaped by stronger Monarchs, who manage a paper-bureaucracy, and standing gunpowder armies, the paper sets the stage of its main subject, while establishing possibility for wider contextualisation. It then progresses to an introduction of the formation of the 'royal houses' of Henry VIII and Ivan IV, with a brief resume of their families 'road', to the power that the Monarchs would wield. Both monarchs temper and subdue the noblemen that surround them in order to ferment their own power-base. Their methods were brutal and efficient. Whether the opponents of the Crown were executed by boiling alive, drawn and quartered, or any other number of imaginative methods, the principle seems to be the same with both Crowns: Maintaining order by demonstrating power, through the application of violence.

Simply: Installing Terror. The Technical breakthroughs of the time enabled the ruling of larger territories, accompanied by centralization of power, not seen in Europe since the decline of the Roman Empire. This then also called for a restructuring of governance. Parliamentary systems are reformed to adapt to this reality and, are re-functioned to act as management organs of the Crown. At the time none of these Parliaments are embryonic 'democratic' institutions, in the modern sense of the word, but they function as a line of communication between the Monarch and the Commoners. Their main function is however to recognize the laws of the Monarch, and to effectuate the levying of taxes. The taxes are in both cases intended to serve the foreign policy of the King. - The protection of the realm; the execution of war-craft. Differences occur in the detail of how Ivan and Henry chose, or can choose, to fill their 'war-chest', and there is better method to the plan of Henry. He implicates part of his loyal nobility in his robbery of the Church, while Ivan's Oprichina leads to the estrangement, and tempering, of his high nobility. The funds from their respective heist, do however go towards the same purpose. They carry the war to their enemies, subduing them, plundering, and gaining dominance of even larger tracts of land. By the crack of the lash, and the screaming of cannon, with bloody sword in one hand, and a pen in the other, surrounded by rich palaces and poor peasants, gibbets, and henchmen, proto-bureaucratic states were formed, both in England and in Russia. They were materializing in all of Europe in the period.

Comparing two reigns of respectively forty-three and sixty years, of almost continual warfare at the western rim of Eurasia, called for an eagle-perspective in this paper, that ignores detailed differences in the formation of Russia and England, which there of course are. The grand lines of the narrative of the paper, however demonstrates that there are remarkable similarities in the formation of Russia and England. Russia is in its proto-state's functioning, during the period of the 16th century, more alike, than unlike England.

So, if you have taken the time to read through this whole paper, what are your thoughts? Any disagreements? What did you like and feel like you learned?

2014/03/21

Did the Russian State... Part XIII by Nils Johann (A Bloody Trail of Death and Destruction?)

"I am a Christian and do not eat meat during Lent", said Ivan to him. "But you drink human blood," the saint replied.”

Body-count competitions are rather tedious. To manipulate statistics is not hard, and to make them with fragmentary sources, that have been 'scrubbed by the sands of time' is profoundly suspicious. It is however done, and the results are used as “facts”, to hammer in one or another point. Both Ivan and Henry killed challengers to their regime. Real, or maybe imagined challengers, but that is beyond the point. Doing so keeps others 'in line'. Crummey makes a number out of foreigners being shaken by the sight of the executions. No doubt they would have been as shaken by witnessing the 'drawing and quartering' of an English Abbot, as by the impaling of a Russian Prince. Being foreign would have had less to do with it. Impaling might sound gruesome, but is it worse than starving to death in an English gibbet?

The Bishop of Lisieux (Lexovia), claimed that Henry had over 72,000 great thieves, petty thieves and beggars executed during his reign.“For there is not one year wherein three hundred or four hundred of them are not devoured and eaten by the gallows in one place or another”. It is not impossible considering the duration of his reign. It would mean about 2000 in an average year, with a stable population of about 2.8 million. It was custom to garotte or hang even petty thieves, and the 'mop-up' after the dissolution of the monasteries and the rebellions, with the loss of poor-relief from the monasteries, could have added the rest. It is however hard to consider the fragmentary hearsay, as a reliable source. It is a domestic estimate, and for diversion we could surely by far double the number by adding the ones that died in the many wars, acts of immense cruelty, with its content of rapine, murder and pillage.

Another example in this manner, from Russia, is the punishment of Novgorod, exacted by the Oprichniki of Ivan. Skrynnikov had the surviving prayer-lists of Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, that listed 1505 names of wealthy citizens killed. He assessed 2-3 thousand killed in total. This number could surely as well be inflated by Ivan's many campaigns.

But this chapter shall not become a competition of cruelty. By my standards, they were both cruel. But it is at least in part, a measured cruelty with an aim, like Machiavelli prescribes -if we look away from the occasional killings of family-members. Maybe, especially Ivan, who struck his son and heir dead in a loss of temper. But also Henry, who used his state to kill several of his wives, after the formalities of a 'kangaroo-court', with himself as judge. Like Crummey writes about 'Mad Czar Ivan' basing his claim on the cruel manner of the Czar's politics, there are publications to the same effect, but not as full with regards to Henry's style of government. When it comes to the understanding of the cruelty of Monarchs, this perspective disregards something in the understanding of social and political power. It may have gotten lost by the peaceful, sanitized, life that most 'Westerners' enjoy. George Mac Donald Fraser's figure, H. Flashman, gives an interesting interpretative perspective:

“...I've heard some say that she [Ranavalona I of Madagascar (R:1828–1861)] was just plain mad and didn't know what she was doing. That's an old excuse which ordinary folk take refuge in because they don't care to believe there are people who enjoy inflicting pain. "He's mad," they'll say - but they only say it because they see a little of themselves in the Tyrant, too, and want to shudder away from it quickly, like well-bred little Christians. Mad? Aye, Ranavalona was mad as a hatter, in many ways - but not where cruelty was concerned. She knew quite what she was doing, and studied to do it better, and was deeply gratified by it,...”

When 'push comes to shove', 'Power' is held by the application of 'Violence'. Being able to harm other people demonstrates social dominance. Being able to harm great numbers of people, demonstrates, and communicates, great dominance. It is (too) easy to declare cruel people to be mad. Another perspective on madness, would be that you are only mad, if you damage your own position. -Harm yourself. Public torture is a matter of communicating with society at large. Our Monarchs had no other option for maintaining their order. There were no logistics or alternative methods for it, as the surplus to afford them only become unleashed with the steam-engine. What Crummey describes, as Ivan's paranoia, leading him into destructive experiments, and a reign of terror, seems to be a 'public management trend' among all rulers of the time, suffering kindred material realities.

Being perceived as mad by your opposition is also not, a all in all, bad thing. It usually just means they can not predict your actions or 'read your mind'. A modern example of this could be the 'brinkmanship' of the Kennedy administration during the 'Cuban Missile Crisis'. And 'Terror' can still, even in the modern 'West' be a ruling instrument, as it is elegantly demonstrated in Adam Curtis' work, The Power of Nightmares, even though it, as a tool, has been refined somewhat over the years.

Our two rulers might have been slick, brutal bullies. Merciless, but must they not also have been charismatic and cocksure? Most likely good orators. With a life full of surprises, and uncertainty, doubt, and fear? They grew into their position of power. They surely were remarkable, to be able to sustain themselves, develop their realms in what was, by no doubt hostile political environments. We can of course meet the stories as those mentioned above with moral outrage, over the 'bestiality' of such persons, and try to spin a moral tale out of their deeds. But if this was their way, the simple question that should be posed is; When those who succeeded, all waged war in this manner, and ruled by murdering their opposition and killing who resisted them, can we then judge such men as Ivan and Henry for surviving?

Comments? Thoughts?

2014/03/19

Did the Russian State... Part XII by Nils Johann (Father of all Things)

“Lupus est homo homini, non homo, quom qualis sit non novit.”

As discussed up to this point, the reason for the acts of our Monarchs, amount to the end-goal of being able to finance, and field their war-machine. War was, during that age, the normal state of affairs. Both Ivan and Henry fielded gunpowder armies, with a core of drilled regulars. It is hard to find a great difference in the way the Monarchs ran their campaigns, or in how they treated the

conquered.

Ivan's cruel treatment of Novgorod is held up as an extraordinary example of cruelty. What seems to be forgotten is that it remained common practice to treat resisting fortresses in a cruel way, if they during a siege resisted, up until the time that the breaches had to be stormed, even throughout the time of the Napoleonic Wars. 'The Hundred-years-war' had started with the 'English' sack and slaughter of Caen. Henry VIII continued this tradition. It was done in this manner, because it was quite costly in human resources to storm a fortification, and thus the example made of an resisting city, should encourage others to not resist. (We could take it further and say Coventry, Dresden, Hiroshima, Ho-Chi-Minh, and Fallujah, are a few of the cities that fell to the same principle during the last hundred years, even though the means of achieving the slaughter had changed.) An almost contemporary example would be Ferdinand II Habsburg's razing of Magdeburg (1631) during the thirty-years-war (1618-1648). His Field-marshal Pappenheim later wrote:

“I believe that over twenty thousand souls were lost. It is certain that no more terrible work and divine punishment has been seen since the Destruction of Jerusalem. All of our soldiers became rich. God with us.”

Henry had a long going hostility with the French 1511-15, and in 1521-25,torching and plundering the land from Calais to Paris. And then again in 1543-46, after the sack of The Church had filled the war-chest again. In conjunction to this Henry employed tactics similar to those of Ivan. Scotland and Ireland were at the time not yet firmly dominated by the English Crown, and the Scottish Parliament favored close ties to the Valoais-French, in order to contain English aggression and dictatorship.

For Henry VIII, a war against the French would entail the potential for Scottish intervention throughout his reign. When the Scottish Parliament revoked the 'Greenwich peace-accord' (1542-43) because, amongst several grievances, it intended a marriage between Mary I (*1542-1587) and Edward, Henry's son, Henry sent his March-Lords north to wreak havoc and punish the Scots (1544-50). The Earl of Hertford and Viscount Lisle, stood under direct orders to raze Edinburgh and they turned a great many towns, cities and the countryside to ash and ruin.

"English policy was simply to pulverise Scotland, to beat her either into acquiescence or out of existence, and Hertford's campaigns ... reign of terror, extermination of all resisters, the encouragement of collaborators, and so on.”

Ivan waged war in two general directions during his reign. South-East, down the Volga Valley, and towards west, in order to gain a foothold on the Baltic shore. The southern conquest of the Nogai tributaries, Kazan (1552) and Astrakhan (1556) were among the early successes of Ivan's reign. The dynamics induced by the expanse of the steppe was a long going, back and forth struggle, but by the taking of the two cities, a better possibility for the containment of the enemywas created. At first the paperwork, and a puppet government were put in order, to legitimize the Russian claims on the area. The Russians came to 'help', and after politics, they let the guns 'do the talking'. The siege of Kazan was an exercise in the gunpowder-siege-warfare, signifying of the age, with a breach being made by sappers and artillery bombardment. The Russian forces were resisted to the bitter end. The cease of hostilities only followed, after the last defenders within the citadel took to flight. The customary pillage, and the murder of survivors, was topped by the destruction the city’s libraries, mosques, and archives. Several years of 'counter-insurgency' within the area followed as well. Four years later the time had come for Astrakhan. Its rulers might have gotten the example statuaeted with the sack of Kazan. Gaining sight of the Russian avant-guard Dervish Ali Khan, who had been sitting unsteady for many years, fled with his forces to the Turks. The city in the Volga-delta was captured without a fight. The area remained contested by the Ottoman Turks for some years, but accord was reached in 1570 after a failed attempt by the Turks to capture the modern Russian kremlin guarding the city. The conquest of Kazan and Astrakhan was to serve as the Russian 'gate' to oriental trade, and to facilitated further expansion into Siberia.

2014/03/18

Did the Russian State... Part XI by Nils Johann (Their Great Heists)

Henry's father had already appropriated the holdings of prominent opponents in the past, stealing land under the guise of legality. Already during the prominence (1509-1529) of Cardinal Wolsey (who at the same time was the Papal Legate to England), the dissolution of thirty monasteries had taken place (1525-6), under the charge of 'corruption', their estates fell to benefit The Crown. This can however only be seen as inspirational pilfering, compared to what was to follow. Facing tax-rebellion and strikes by 1525, and having exhausted the state's economy for prospects of re-conquering English claims in France. Henry had no other choice than to seek peace, putting at rest military ambitions for the following decade, until he, and 'Lord keeper of the Privy Seal' Thomas Cromwell, (*1485–†1540) 'lash out' against The Church. The Acts of 'Suppression of Religious Houses' were forced through Parliament from 1536 up until 1539. In 1534 Cromwell had established an office that made a tour of appraisal, to estimate the worth of the monastic holdings. The holdings were made up of about a quarter of the real-estate in the realm. They started by appropriating the smaller estates. This spurred quite a large resistance. Resistors were to be gibbeted, hung, or drawn and quartered. This amounted to a larger rebellion. After it had been 'struck down', all ringleaders were executed, even though pardons had been offered and their demands had been accepted. To establish credibility the Abbots of Colchester, Glastonbury, and Reading, were hanged, drawn and quartered, and many were harshly punished and killed for their treason. The premise was established for further seizures. When it was finished, over 800, of about 850 monastery-estates, had been appropriated. The 'Coffers' of The Crown were now filled for military campaigns. But Henry still waited several years, most likely because of the internal disruption the attack on The Church had caused. This solution to economical problems seems similar to what Ivan tried to accomplish with the 'Oprichnina' (1565-72).

I have not been able to find any specifics on the Russian tax-codes of the period, but the sheer logic of the Oprichnina gives the impression that there were similar principles for allowances to monarchs in Russia, as in England, and other 'emerging bureaucratic states' throughout Europe, and maybe further east as well? As the Monarch was the one responsible for foreign policy, he could levy tariffs or tolls on foreign trade and some industries, like mining, and further, in connection with minting or arms-manufacture. Besides this, the Monarch would rely on his personal domain-land to keep the Crown outfitted.

The Oprichnina was set up during a period of intense border-wars threatening to overrun the Russian Empire. It consisted in large part of 'newly' conquered Novgorodian territory and the region of Vladimir. The story starts with Ivan, frustrated by the politics of The Capital, withdrawing to Alexandrova Sloboda. There he goes on 'strike', destabilizing the ruling council, and agitating the citizens of Moscow against them. After some negotiation, the noblemen agree to grant Ivan absolute unchecked privileges in the 'Oprichnina-territories to be'.

The Livonian Wars (1558–1583) were in part a result of Ivan's will to expand his sphere of influence, to gain foothold on the Baltic shore, thus avoiding the restrictions put on Russian trade by the powers controlling the Baltic ports. This crashed with the strategic ambition of several powerful neighbors holding a stake in the disintegrating fragmented Baltic territories. The Oldenburg, Vaasa and Jagellionians, with the Habsburg, the Dutch, and the Hansa meddling in the background, wanted 'a piece of the pie'. Tension between opposing forces is a given in power-games. Crummey does overestimate Ivan's role in what was to happen. In Crummey there is a blindness being cultivated towards, that the other actors in similar manner had aggressive ambition, almost as if Crummey postulates, that Ivan could have chosen peace? Statements like that, again make me reach for my Machiavelli:

“The Romans, foreseeing troubles, dealt with them at once, and, even to avoid a war, would not let them come to a head, for they knew that war is not to be avoided, but is only put off to the advantage of others.”

Leaders at times, just must lead, but the lack of proper sources does not stop Crummey from painting a grim picture. In his work the method to the madness of the Oprichnina is to be found in Ivan's sick paranoid mind. Crummey makes it easy for himself when he states, that since the conspiracies against Ivan are so poorly documented, they probably were figments of his imagination.

"The image of Ivan as a paranoiac lashing out blindly and none too effectively is well drawn by Crummey. Undoubtedly the greed, bitter internecine rivalries and self-importance of the Boyars were injurious to the efficient functioning of the administration and contributed significantly to Russia's failures in the Livonian War."

The first thing to say about that is, that if people are proven to be disloyal to you, and they try to get you... you are not paranoid, but you have a healthy instinct for caution and survival. Crummey is at times exorbitantly hostile in his treatment of Ivan. This belittles the direct practical application of this attempt at bureaucratic management. The direct control over resources needed to wage war on the surrounding enemies, gathered in one chain of command does not seem like the plan of a madman, because it in principle is rational, as argued in Pavlov and Perrie, who also further develop the idea of Ivan as a contemporary renaissance-prince.

The Oprichina was however a large land-grab that was bound to threaten the position of all 'Gentry'. They are the main source for description of the event. Gathering large domains in the 'hands of the Crown' theoretically reduced the need to negotiate with the lords and the gentry over the pressing needs of war, aiding to streamline the strategic depth of operations under a clear command structure. In order to enact this 'bold and courageous' change in policy, a new branch of government was formed. Its officials, the Oprichniki, were enlisted from the ranks of 'free-men' while a few were noble. They proved more trustworthy to the Monarch than the Bojar Class, since they had less power and claim, to challenge or obstruct his rule.

Henry and Cromwell had two advantages when they started to plunder The Church. When the land of The Church had been appropriated, it was sold to the loyal segment of The Nobility, firming them in their resolve against The Church, and implicating them in the new order. Their payments then filled the King's 'war-chest'. Henry succeeded, and was ready to subdue the whole of Britain. The other advantage was that Scotland is not The Steppe. It is not a 'never-ending' expanse. It still can make one wonder, if Ivan was not inspired by Henry's success. We know there was direct contact between England and Russia from about 1540.

Judgment on why the Oprichina was dismantled is difficult. Letters written by a discontented mutineer like Prince Kurbsky, portraying Ivan as a tyrant, do not compare to a modern day 'aircraft black box'. It is hard to differentiate the factors leading up to the dismantlement of the Oprichina-system. Was it a system that was internally weakly constructed, or did it fail due do the external pressures of a three front war in combination with natural crop-failure? It is wise to respect that 'force major', nature, is dubbed so for obvious reasons. -that Xerxes had the Hellespont whipped, did not bring his fleet back. That the Crimean Tartars burnt Moscow might have been a tipping-point. De Madriagda suggests that the system might have fulfilled the purpose of breaking the 'grip' of the Bojars. Enough credibility had been established to unite the territories, under a reformed Bojar council which included many of the leading Oprichniki as well. Both the 'Acts of Suppression', and the establishment of the 'Oprichina', lead to an accumulation of lands, in the 'hands' of the Monarch, and to the weakening of his opposition, both nominally and relatively. Neither of the systems permanently gathered the land with the Monarch, but they permanently established a principle of supremacy.

2014/03/17

Did the Russian State... Part X by Nils Johann ('Some of us have talked...')

'Parliament' is the normal consequence of people trying to live together, and the English alone, developed neither of those two concepts. Neither did Ivan IV invent it in Russia. Communities meet to talk, and decide on matters regarding the community. The 'Veche' in early mediaeval Russia, preceded the Russian state-formation, and it worked as a Forum, for talks on economics, law and war, like the Norse Thing or the Swiss Landesgemeinde. The free cities of Pskov and Novgorod are often held up as later examples of these kinds of assemblies. None of the assemblies, like the Veche, or Parliament were open to everyone. We need to keep that in mind, before we start to romanticize a pragmatic tool of government. They are fori, where those who have franchise in the state, -those who contribute directly to the state, meet. “Taxpayers” in one form, or another; warriors, landowners, merchants and master tradesmen. Those who possess a vital skill or a business. After the gathering of the dispersed territories under Muscovite rule, these forms already in existence, were utilized by Ivan IV. He used it to govern and organize his realm, and he enacted reforms of many sectors of state. Opinion on how Ivan's Zemsky Sobor worked differ, from that it was a puppet parliament, there to enact his will, to a (sometimes) legitimate channel of popular representation. Crummey states,“...it would be a mistake to view it as an embryonic representative institution.”

To counter the claim in Crummey: It would be a mistake to see the English parliament aslittle more than a constant Byzantine court intrigue.

If we look at how Henry used his parliament to shore up the power of the Crown, there is however no great difference to Ivan's use. And here a special understanding is needed, because this will seem odd to those of us, accustomed with a modern parliamentary system. It needs to be seen in regard to the justification for power, being derived from 'Divine Right', and thus parliament gathers with the Monarch, for him to explain how he understands the will of God, and for them to agree that his interpretation is correct. And who wants to anger the Warlord who runs the “legal” punishment-system? But with this in mind, inevitably the system must have communicated in both directions. (*To relate Crummey's statement to a anachronistic example of representative government, the United States of America might serve. Even though regulation varied across the states, on average 5% of the adult population maintained the right to suffrage. The right to representation was restricted even more, but the representatives were deeming themselves as representatives of the entire populous. )

In order to effectuate policy, and to communicate better with the vast domain of the Czar, he called for 'The Assembly of the Land' in 1549. It was made up by the tree usual estates, The Nobles, The Church, and The (rich) Townspeople and Merchants. This 'Zemsky Sobor' developed to gathering regularly after that, and was also taken to advice on controversial issues. It seems, its main purpose was to agree with (or “understand”) the Czar's interpretation of the will of God, as was the case in England. In addition, a council of chosen nobles, The 'Rada' or a 'governing council' if you will, was established, and the organization of The Church was centralized. The 'Stoglavy Sobor' ('Gathering of Hundred Heads') was used to unify the practices of the Church's rituals and its regulations. Like with the Zemsky Sobor, it was done to streamline the 'chain of command', and to ease management. In rural regions, increased local self-government was introduced. The communal councils were attributed privileges that prior to that had been the jurisdiction of the local noblemen / governors.

One trait was the 'popular' election of local tax-men. Crummey claims;

“The explanation for the Monarch's broad power lies not so much in the efficiency of his government as in the lack of barriers to his exercise of it; for no estates or corporate organizations limited the Grand Princes' freedom of action, and no constitutional norms defined their authority.”

Crummey's work ignores the bargain character of what Ivan builds, as these systems inevitably will communicate both ways. Further on, the work also ignores that there is Law, and that the system of Ivan seems to be a “normal” Divine-Right-Monarchy for its time. Even more remarkable, is Shepard's comment in his review of Crummey, when he concludes on the basis of Crummey's work;

“But at the end of Ivan's reign, after all the blood-letting, he still ruled with the collaboration of the clans of the higher nobility, and for the most part these were the same clans that had been pre-eminent in the opening years of his adult reign!”

It is a interesting contradiction to take note of. If there is cooperation with the high-nobility within the Rada, how can it be that there are “no estates or corporate organization” to limit the Grand Prince? The 'Zemsky Sobor' was also a tool for achieving cooperation, and this does not differ greatly from the English 'Parliament' during the period.

Henry needed capital to wage war for his dynastic claims on the continent, and to construct palaces. He had emptied his coffers and exhausted the land by the middle of the 1520's. The system of taxation had to be reformed in order to enrich the Crown. The first plan was executed by the King's Minister, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (*1473–†1530), who managed to gather funds through an increase of the tax-burden on the wealthy, land-'theft', and by forcing the nobility to “buy” a kind of prototype state-obligation.

As we remember from Spittler's definition above, we are here looking at two semi-bureaucratic states where income comes from personal agricultural landholdings, and to a minor extent from the tariffs on foreign trade. Both monarchs, next to the tariffs on foreign trade, gain their means from their personal land-holdings. For any further taxation, the security of the realm needed to be at risk. This would also have been the main reason to call together 'Parliament'. The dominant reason for any self-respecting monarch to talk to a 'Common House', would have been to enact special taxes, without too much resistance. (This might be a motivational factor for the constant warfare of the period. Special taxes would have to be justified, as issues of defense of the realm. It served the concentration of capital, and the centralization of co-ordination, to the Crown.) However, if he could, the Monarch would avoid the hassle of having other people telling him how to run his 'firm'.

This takes us then to the great heist, performed in a similar way, in order to achieve similar ends, by both monarchs. The details of course differ, but Henry and Ivan do come to a remarkable solution to their challenges, regarding organizational and financial autocracy. Their goal is it to reduce dependence of people that are not necessarily to be trusted, discipline their own rank, and to gain a higher degree of fiscal independence. The Monarchs' role as Primus Interpares was changing in many emerging states during this time. As the positions become more polarized, we see the emergence of Autocracies (Denmark, Russia, Iberia, France, and England until the civil war), and their counterpart, noble-republics (The Netherlands, The Swiss federation, and to some extent also Sweden and Poland,).

2014/03/16

Did the Russian State... Part IX by Nils Johann (Give to God what is God's, and to the Emperor what is the Emperor's.)

“It must be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to plan, more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to manage than a new system. For the initiator has the enmity of all who would profit by the preservation of the old institution and merely lukewarm defenders in those who gain by the new ones.”

In their approach towards the church, our two Monarchs differ. This is due to the difference in the power-structuring of the Catholic Church, and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Both rulers of-course demonstrated devotion in public rituals, like Henry’s 'pilgrimages' or Ivan's traditional conversion to monastic life, at the end of his reign. But then there were the challenges of Realpolitik. Henry wanted a servile Church that did not challenge his authority, and he needed cash. Ivan, in part already had the Church that Henry desired, through the traditions of the Byzantine Church and the affirmation of his title as 'Czar'.

Within Orthodoxy, the State-Church was at this point already well established. The first 'Non -Roman' case is when the Serbian Kingdom gained its Church's autonomy by 1219. The ratification of the Zakonopravilo enabled the King to rule as if he were 'Czar' (Emperor), and thus also to rule the Church. The Zakonopravilo, or Νομοκανών (nomo-canon), was a revival of Roman codex tradition from the time of Justinian I (*482-†565) in combination with other church-law. It was produced by St. Sava, in the Mount Athos Monastery. The law became widely dispersed within the realm of Orthodoxy, at first as a manuscript, but printed editions from Moscow in the 1650's have also survived. At the time of Ivan it was taken to be self evident that the Monarch was the 'Pastor' of the Church. In Ivan's first letter to Kurbsky, dated fifth day of July 7072 A.M. (1564 A.D.) Ivan claims to rule in the tradition of Constantine, and, that those who oppose power like his, also oppose God who has ordained him with it. This does, however, not mean that the leaders of the Church always were unison with the Princes. Ivan would also use brute force to root out contemporary resistors within the Church. Laws from 1572 and 1582 expressively made it clear that the Crown had the right to manage Church-Land. This was most likely a consequence of the State's war-exhaustion.

In a rather rustic example of bending excuses in favor the “backwards-narrative” Sugenheim can remind us of the “moral superiority” of the 'Catholic' Church in comparison to the Eastern 'Orthodoxy'

-”Because it was nothing else than a, from servile priests without a conscience, for the moods and needs of the vices of the most heinous court of the world, masquerading under the name of Christianity.” -

And he makes this just as strong an argument as the Mongol invasion for explaining the contemporary “backwardness” of the Russian state... that the Church was a tool of the State? It is an old publication, but it stands well in line with other invented absurdities to make Russia different, as it does not industrialize at the same time as England. One can only wonder how Sugenheim would explain the contemporary British hegemony, with regards to the Crowns dominion over The Church of England?Further it opens the question if the cradle for the story of Russian backwardness does not lie in the defeat in the Crimean war (1853-56)?

For western monarchs, it had for a long time been a problem that the Church operated autonomously, (but) in alignment with 'the powers that be'. The Popes in Rome, as did other Monarchs, start to hold 'in their hand' a good bureaucratic system - large landholdings, producing an enormous wealth, and a communication-network. But they had a constant “security issue”. Henry’s poor luck with his wives, and the Pope's refusal to grant him divorce from Catalina de Aragon, who had strong family ties to the House of Habsburg , is often brought forward as a rather 'folksy', (mass-communicable parole,) excuse for the English State's break with The Church. The break was made law in the 'Statute in Restraint of Appeals' (1533). However, the English State was in a constant tense relationship with its two neighbors across the channel. Valois-France, a budding great power on the continent, next to little England... and The Habsburg, trying with some luck to manage a large part of the rest, while running their growing over-seas empire. France had a standing army and the “Most Christian” French Monarchs were expanding their influence on the Italian Peninsula. While the Habsburg, often carrying the title “Defenders of the Faith”, also were just 'next door' to The Holy See. The Holy See was far from immutable by foreign pressure. Pope Clement VII (R:1523-34) was even at time, prisoner of H.R.E. Carl V Habsburg (*1500-†58). The Church’s claim’s to ultimate universal supremacy (e.g. : Catholic), next to the statement of infallibility, made it a liability to those powers, that could not simply come by, to extort good will. (- Like all “Lutheran” rebel-states?) The Church in the North had also grown rich, as it had been the most clever 'firm' around a long time, further heightening the temptation to be acted against.

In his letters to Anne Boleyn, Henry speaks of himself as Caesar, following this he puts his imperial ambition to show, measuring the strength of his office with The Church and The Pope in Rome. Imperial is here to be understood in the sense, that the Emperor has no master, no-one to dictate to him what to do. The titillation implies that the holder is the unchallengeable 'fountain of law', giving the office-holder the universal ultimate word within their dominions.

The 'Statute in Restraint of Appeals' (1533) in combination with the '(First) Act of Supremacy' (1534) are trumped through parliament. They effected the banning of paying any dues or tides to Rome, and the right of judicial appeal to The Pope.

“...this realm of England is an empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one supreme head and king, having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial crown of the same...without restraint or provocation to any foreign princes of potentates of the world.” The latter act states directly that The Church is subject to The Crown. “...the King's Majesty justly and rightfully is and ought to be the supreme head of the Church of England...”

Thus Henry VIII achieves for England what the Rus Princes have had arranged for 'quite a while'.

2014/03/15

Did the Russian State... Part VIII by Nils Johann (The Circumstance of the Two Ruling Houses, and their Nobility)

“And men have less scruple in offending one who makes himself loved than one who makes himself feared; for love is held by a chain of obligation which, men being selfish, is broken whenever it serves their purpose; but fear is maintained by a dread of punishment which never fails.”

Henry VIII Tudor (*1491-†1547) took the throne in 1509 as a young man, 17 years old. He was not supposed to become king, but his older brother, Arthur, had suddenly died. Leading up to this point in time, England had been a unruly place, where only 25 years earlier, feuding nobles had been tearing the realm apart. The House of Tudor, was the product of the alliance by marriage of the Houses of York and Lancashire in 1486. A compromise that symbolically ended the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485). They had been in open conflict since 1399.

These Wars of English succession, had happened shortly after the wars for French succession, also known as the 'Hundred Years War'. The 'English' (Normans) withdrew from the continent and relinquishing their prospects to gain the French Crown. The wars had strengthened the Crown, vis-a-vis the Barons, establishing large military forces under direct control of the Monarch. Having standing armies is of course expensive and having them, it probably did become a great temptation to utilize them in order to 'resolve' the claim to the English Crown. Henry’s father Henri VII Tudor (*1457–†1509) had won the title of King by waging war on Richard III (*1452–†1485). He was killed by Henri's henchmen during the battle of Bosworth field in 1485. Henri had after that, tried to confiscate all lands belonging to supporters of the late King, by declaring himself King retroactively, making his opponents traitors. During Henri VII's reign, he four times faced larger rebellions by the Barons, triggering a crackdown on their right to keep 'private security forces'. Harsh realities like these are not easy forgotten by the young King and his advisers, and one can in his actions during his reign, see a constant maneuvering in order to keep the nobility at bay.

One of Henry VIII first actions was to 'cleanse' the Nomenclature of The Crown, of some his father's advisers that he disliked. The Yorkist 'White Rose Party' could still challenge Henry VIII for the throne and in 1513 he had Edmund de la Pole, the leader of the 'Party', murdered. Henry constantly worked to intimidate the members of the high nobility. In the following years he also had Henry Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk and Buckingham, indited for 'treason' by his Minister, Cardinal Wolsey. He had Brandon murdered in 'The Tower'. Wolsey would in the end suffer the same faith, and the same is true for the man who was to fill his place, Thomas Cromwell. The corpses in gibbets, or the head of these “traitors” on a spike, would often greet visitors who entered London through Tower Bridge. It shows the ambivalence of relations, between the Crown and its supporting nobility, as we enter an age of more powerful monarchs, that are increasingly able to rule without the political support of the high nobility. This tendency, we can also observe in Russia. From 1237 until 1240 the Rus princes had been overwhelmed by the conquering Tartar armies of Batu Khan. Kiev, the cultural capital of the region was razed. Other parts of the region, like Moscow, were only sacked. The Rus Principalities were made subsidiaries to the vast empire of the Golden Horde. In the same period the cultural centre of The Orthodox Church, and the central trading partner of Kiev, Constantinople, had been conquered and occupied by Latin “Crusaders” from 1204 till 1267. During the suzerainty of the Horde, a small difference in the customs of inheritance in Moscow allowed for the most eligible prince (though usually by primogeniture) to inherit the major share of property, unlike other parts of the region where every heir got an equal share, and the estates were divided.

By the time of Ivan III (*1440-†1505) the Tartar suzerainty was beginning to properly disintegrate. The Horde had started breaking up into several feuding parties after an interregnum in 1410. He exploited the situation to further expand the dominion of Moscow, unifying a vast Rus territory under his rule. In 1472, he took as his second wife, Zoe (Sophia) Palaiologina, the niece of the last Roman Emperor. The family-crest of the Palaiologians, the double-headed eagle was adopted by the grand princes of Muscovy. In addition to bringing with her a grand number of technocrats, there was also the baffling amount of eight-hundred books in her baggage, further strengthening the technocratic bond between the 'Second'- and 'Third Rome'. The library is supposed to have contained works of law by Constantine 'The Great' (*272–†337), and Justinian I (*482-†565), and several 'princes mirrors'. Vasili III (*1479-†1533) son of Ivan III and Zoe took several steps at defining his reign as continuation of the Roman Empire. In Zoe's retinue followed, artists, physicians, and politicians, who were well connected to the general developments elsewhere in contemporary Europe. There are many cases of integration of both, talented Greek refugees and other artist coming to the land. It is interesting to note the both Henry and Ivan, amongst other precedence, base their claim to autocracy on the Roman Law of Constantine. The Byzantine influx spurred after the fall of Constantinople in 1204, may very well have been a large contributing factor to the Renaissance, as Roman-Greek technocrats traveled westward, and northward.

Ivan IV is born near Moscow on August 25th 1530 as the only son of Vasily III. His father passed away when Ivan was only three years old. By the leading Bojars, Ivan was accepted as the legitimate heir to the throne. He was proclaimed Grand Prince of Moscow, while his mother Yelena Glinskaya acted as Regent in his place. After Ivan had turned eight she died. Maybe naturally, maybe by poisoning, initiated by a noble faction biding for power. Other different factions in court started biding for power and influence. The next decade was a time of political turbulence in Russia. Three, and at times more, Bojar 'parties' used this period to try and gain political superiority over each other. They gravitated around the families; Shuiskii, Bel'skii, and Glinskii. Ivan had been eight years old, alone, and at the same time surrounded by power-grabbers pretending to the position of Regent. They had schemed, plotted, and murdered, and used violence to attain their goals, and thus it is possible that the nobles had made a bad impression on the young Prince.

Ivan had slowly started to take command as Grand Duke at about age thirteen. It seems that Ivan stemmed the bickering, by having a Shuiskii Prince torn by his hunting-dogs in the Kremlin- Square. In political terms, we call that establishing credibility. Just like Henry, Ivan had to use force and terror to get his Barons in line, in order to lay the foundation for future negotiation.

After he turned sixteen in 1547, Ivan was Crowned as the first 'Czar of all Russians'. In the first years of Ivan's reign, reforms were made to gather more power around the Sovereign, centralizing government and formalizing and reformulating acts of government. Like in other domains in Western Europe, a move away from feudal structuring towards an attempt at central bureaucracy was in formation.

The similarity that we can recognize, in the background of the two rulers, is that their position is the result of preceding conflict between their respective houses, and other noble families. Their realms had been formed by the use of organized violence and were maintained by the use of force...deadly if need be. This is nothing especially original. An anecdote from Herodotus' Histories comes to mind, that might illustrate this. It is a story about Thrasybulus, the Despot of Miletos and Periander, the Tyrant of Corinth. Periander sends a messenger to asks Thrasybulus for advice on ruling, and on how to stay in power. Instead of responding verbally Thrasybulus takes the messenger for a walk in a field of corn.

“he kept cutting off the heads of those ears of corn which he saw higher than the rest; and as he cut off their heads he cast them away, until he had destroyed in this manner the finest and richest part of the crop.”

The messenger conveys what he had seen happen, to Periander, adding that he has doubts about Thrasybulus sanity. The message was still correctly interpreted by Periander; a wise ruler would pre-empt challenges to his rule by removing those prominent men who might be powerful enough to challenge him. “...to put to death those who were eminent among his subjects.”

It is the simple story about how power is taken and maintained and it is foolish to assume that not any person of power operates in this way, because social bonds are fragile. It is perfectly rational for a monarch to harbor some resentment towards nobles because he often would be in economical counter-conjuncture to them. More 'taxes' for the monarch would mean less for the nobles or vice versa. It would also be rational to feel insecure about them as they, (the other wealthy and powerful families,) were the ones the Monarch had to rely on for the stability of his reign. Monarchy (Autocracy) is a 'reference-system' for organization and order, no-one has, or will ever, rule alone.

2014/03/14

Did the Russian State... Part VII by Nils Johann (The Development after the Time of the Black Death)

The Black Death had spread westwards, disrupting the societies it infected. Old bonds were broken and ruling structures were destabilized. Power dispersed, even to the point that peasants were able to renegotiate the conditions of their bondage, as a result of the shortage in workforce, in relation to workable natural resources. Strong central government had not been materialized in the west since the Roman empire contracted eastwards. Coming into the middle of the 15th century we can see a renewed effort among the warlords in the peripheral regions, bordering on Islamic civilization to their southeast, to gather grater territories and to build state-institutions, like stable dynasties and monarchical hierarchies. Barons (*local strongmen) would not cede power easily to pretenders to monarchy. On the Iberian Peninsula, Ferdinand (*1452–†1516) and Isabella (*1451–†1504) fought a decade long civil war against their Barons and succeeded. Matthias Corvinos (*1443-†1490) tried something similar in the area of modern-day Hungary but failed to establish a stable monarchical institution.

Up until 1453 the 'Hundred Years War' (1337 to 1453) had made it easier for the French Monarch to gather his power. The conflicts had introduced the first large standing armies in North- Western Europe since the decline of the western Roman Empire. The armies started to replace the role of the retinues of Feudal Lords in warfare. In the resolving part of the conflict, even zappers, and cannon with iron shot had started to play its part, next to the traditional bowmen, lancer infantry, and heavy knights.

War is in the period the general vehicle for gravitating power towards the King, as the war, as part of foreign policy, gives the King reason to levy taxes, where he usually would only have right to the tariffs and tolls. Standing armies are expensive, and in connection with them, we also see the rise of a bureaucratic tax-system with an annual tax, further increasing the power and reach of the Monarchs. Henri VII Tudor, took in twenty times more taxes, than any of his predecessors since 1066.

Other notable state-formations rising in this period, besides the more peripheral English and Russian, are, the Habsburg Empire, the Jagiellonian Empire(s) and the Ottoman Empire. They were all bureaucratic states with standing gunpowder armies, and the predecessors to still familiar modern states.

The monarchy itself also changes in the period, as the pen becomes mightier than the sword, from bloodthirsty field commander, to a high level paper-pusher. Philip II Habsburg (*1527–†1598), rarely leaves his desks in Valadolid and at El Escorial, in contrast to his father Carl V Habsburg (*1500-†1558), who spent much of his time, personally leading the army in the field. The nobles also lost their traditional role as plated knights on horse. The superiority of cavalry that amongst others also Machiavelli notes in 'The Art of War' (1521), peters out during this century. Cavalry’s expensive, time-consuming, training can be made to nothing, by any peasant wielding a hand-arkebus, in between a phalanx of Landsknechten pike-men, or by field-artillery. Quite suddenly, accompanied by Cervantes' satire, they change form and live on as the less dominant gunmen on horseback.

2014/03/13

Did the Russian State... Part VI by Nils Johann ( A Short Introduction to the Period... 'The Mafia ?)

“A prince ought to have no other aim or thought, nor select anything else for his study, than war and its rules and discipline; for this is the sole art that belongs to him who rules, and it is of such force that it not only upholds those who are born princes, but it often enables men to rise from a private station to that rank. And, on the contrary, it is seen that when princes have thought more of ease than of arms they have lost their states. And the first cause of your losing it is to neglect this art; and what enables you to acquire a state is to be master of the art. ”

In the State-formation histories of Scandinavia and the wider 'West', Finn Fuglestad uses the term “Mafia Society” to describe early state formations. I am partial to introduce that term when discussing state-formations in England and Russia, or anywhere, for that matter. It is a term that should be kept in mind during the further reading. It should be seen in relation to Spittler's definition of 'despotism'. The term describes a situation where strongmen either do, or do not, get along. They cluster together, in order to 'racketeer' in territories they dominate, or they plunder their opponents. Wealth and power in the period are still highly personal, even though the term 'Crown' and 'state' are used at points in this text.

Machiavelli makes a good companion to the period, and his contemporary work delivers a good description, rather than a normative tale. His work marks him out, as a sign of change taking place, as Berg Eriksen writes in the foreword of his translation: “The possible restoration of Roman

power [e.g. a strong bureaucratic state] in Italy would be the newest thing imaginable”. 'The Prince' has proven itself as a stable control-guideline for the comparison.

Moreover, we can in the period, see new attempts at institutional bureaucracies next to the person of the Monarch and his 'Bojars'. This paper will demonstrate, how Ivan and Henry established internal discipline within their organization. We will look at how they both ran their 'firms'. In both the territories work starts to effectuate a more efficient tax-system, and state

institutions are established to carry this out.

2014/03/12

Did the Russian State... Part V by Nils Johann (Why, and how to compare the Rule of Henry VIII with the Rule of Ivan IV?)

Maybe the best way to clear the question, of the comparability of the formation period of the Russian State, is by comparing more or less contemporary case. Noam Chomsky formulates this approach in several of his publications but the most elegant formulation stems from“Manufacturing Consent”(1992):

“Interviewer: I'd like to ask you a question, essentially about the methodology in studying 'The Propaganda Model' and how one would go about doing that?

Chomsky: Well, there are a number of ways to proceed. One obvious way is to try to find more or less paired examples. History doesn't offer true, controlled experiments but it often comes pretty close. So one can find atrocities, or abuses of one sort that on the one hand are committed by "official enemies", and on the other hand are committed by friends and allies or by the favored state itself (by the United States in the U.S. case). And the question is whether the media accept the government framework or whether they use the same agenda, the same set of questions, the same criteria for dealing with the two cases as any honest outside observer would do.”

As long as 'The Cold War' lasted, it may have seemed like there was a definite line separating “Eastern” and “Western” culture. The global political power-struggle that took place, did, or at least it seems to have, overemphasized difference. Most likely this dominantly happened as a conscious relation towards the conflict by the authors, and to a lesser degree because of the restricted opportunities to communicate and cooperate across the political divide that was formed by 'The Cold War'. It was primarily a power-political divide, but not necessarily a clear cultural divide. To most conflicts between any given parties, a certain animosity will follow. It becomes easier to dehumanize the enemy, and this is done by starting out, to look for differences, not for

commonalities. Dichotomies that support this attitude of animosity have to be found out and cultivated. When these differences are cultivated and (over)exaggerated, they will after time be held to be basic truths, and misinterpretations will happen.

Surely the period we are going to discuss; Russia, roughly from the 15th to the 17th century, is somewhat removed from the issues of the 'Cold War'. But the 'Cold War ideology' may have been lurking in the background, in the consciousness of the historians interpreting. Even if there is an honest appreciation for historical facts internalized in the scholar, this is not in itself a guarantee for an accurate assessment of the past. At least not in the environment of contagious anti-communism, before, during, and after the time of the Soviet Union.

This paper is not the first attempt at comparison. Edward Keenan already deemed it futile back in the 70's, to find any means of aligning Russian history, with its “European” contemporary counterpart. But for those who have seen his works, it becomes clear how concerned he was with “detail”. In Keenan's world there was not much room for comparing anything. Michael Cherniavsky, Halperin's mentor, however inspires an attempt at comparison, portraying the traits that make Ivan a proper “renaissance prince”. There are many traits that offer themselves as similarities.

There is no question that Russia is different from Britain during the 16th century, just like every other institution is different from the next. The biggest difference between the two units might be the size and the geographical attributes they contain. In the time, transport by boat was far more efficient than overland travel, giving a comparative logistical advantages to the English. They are surrounded by the sea, whilst the Muscovites were depending on their river-systems, to connect an area that in average was far less densely populated than England, and at least, ten times more expansive. Further difference is that far more sources have survived in England. Wooden Moscow was 'put to the torch' several times by various enemies. In addition England got its first printing press in 1476, while the first Muscovite press was set up in 1553. English sources are also more widely accessible to western scholars, than sources written in Russian variations.

Arguing for a Sonderfall still might not be the most fruitful thing one can do, even though, I must admit it could be done in any case, regarding any institution. -The refusal of the abstract concept of the forest, in favor of our favorite tree. The Crowns of both Henry and Ivan, handle their opponents and the nobility harshly, they constantly make war and their finances suffer. The way their respective parliaments function seems kindred. Behaving like prototypical Autocrats, both are good examples of the ruling-style of their period, being held up as the best form of government in Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil (1651) about a hundred years later.

Labels:

absolute monarchy,

autocrat,

Cold War,

communism,

dehumanize,

England,

Great Britain,

Henry VIII of England,

Muscovite,

Nils Johann,

Noam Chomski,

politics,

propaganda,

Russia,

Soviet Union,

Western Civilization

2014/03/07

Introduction to Nils Magnus Johann and his Research and Writings on Russia

Boy, do I have a treat for my history loving friends! I am very excited to have the opportunity to be able to share a paper from a friend that I met online who also loves history. This is an amazing paper – well thought out and researched- and I feel honored to introduce him and his work to my readers! :)

I apologize that I do not have a good biography of the author yet, but I hope to soon and I will upload it when I can. I need to break up his post into several parts, but I will post a few pages a day so that there is continuity for those who are interested in reading it. Please also feel free to leave comments of feedback and I will make sure that he gets them! So with out further ado, here is the title and a short tidbit of what the paper will cover over the next week or so. So let's begin!

Did The Russian State Form in a Different Manner than Its Occidental Neighbors?

Can Russia be seen as following the same formative patterns as the new, bureaucratic (proto-) states rising in Western Europe? A discussion in historiography, world history, and the problems of long chains of causality, exemplified by a comparison of Russian and English political history during the reigns of Ivan IV and Henry VIII. (Late medieval/Northern Renaissance, period, 16th century.)

Introduction: Did the Russian state form in a different Manner than its Occidental Neighbors?

On the 'Curse' of the Orient.

The Myth of 'Oriental' Despotism».

On the 'Miracle' of Western Europe.

Why and how to compare the Rule of Henry VIII with the Rule of Ivan IV?

A Short Introduction to the Period of the Comparison. ('The Mafia-Society'.)

The Development after the Time of the Black Death.

The Circumstance of the Two Ruling Houses and their Nobility.

Give to God what is God's and to the Emperor what is the Emperor's.

'Some of us have talked...'

Their Great Heists.

Father of all Things.

A bloody Trail of Death and Destruction?

Conclusions.

Labels:

bureaucracy,

Education,

England,

Henry VIII of England,

historiography,

history,

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (the Terrible),

medieval history,

Nils Johann,

patterns,

politics,

Renaissance,

Russia

2010/04/17

Perception and Reality

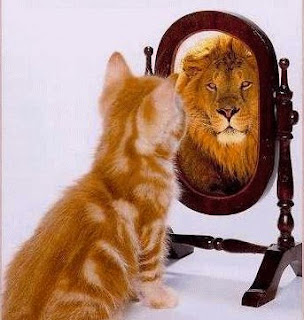

Isn't it funny that a few people can share a day together and then go their separate ways. The next day two of the members of the group that shared the same exact experience can 'see' the experience so differently from the other person. In fact, if you didn't know better, you might possibly come to the conclusion that someone is lying to you. But in reality how each individual processes their day in their mind made the experience different due to their perceptions.

The word perception in regard to human psychology is usually defined as the process of attaining awareness and understanding of sensory information. How a person perceives their situation, environment, etc... is almost always affected by several factors- past experiences, culture, interpretation of past and cultural events, age, intelligence level and more. Rene Descartes hundreds of years ago conceived the idea of passive perception that can be described as a series of events; input (senses), processing (brain), and output (reaction). Today, many psychologists tend to subscribe to the idea of active perception as a more accurate way to describe the idea that there is a dynamic relationship between the brain and senses which create experience.

So even if every human being is exactly the same in all ways (which of course we are not), we would still find that people's perceptions will differ from each others. If our genes were exact duplicates – in essence, if we are clones- our experiences might be slightly different causing different perceptions and ideas. I find this idea so fascinating and frustrating all at once. It is fascinating because the world is an amazing place with so many differences in people, environments, cultures, etc... Look at the amazing people we learn about in history class and how our world has been shaped by their perceptions of the world around them? One example that springs to mind is Henry VIII of England. Even people who have no interest in history have heard of this king/man. His perceptions of himself, gender and reproduction changed the lives of his many wives (sometimes ending their lives), the lives of his children and the lives and culture of an entire country. One of his daughters Elizabeth I went on to rule after him and her perceptions of power and men again changed the course of her life, the lives of all those around her and the history and succession of an entire country.

However, one thing that really frustrates me about perception is that we as human beings can be so shuttered and trapped into poor perception. When we are born, our brain in many ways is a blank slate which we then begin to fill. As we get experience in life, this experience will change and therefore bias our perceptions- there is now a preconceived concept. This happens because human beings do not readily understand new information without the bias of their previous knowledge. So we can misinterpret others actions and behavior based on the actions and behavior of others that surrounded us in the past which can cause us problems in our present. Or,maybe even worse, we can fail to perceive something at all because our brains are unable to process the information in any way. So something can be explained to you a million times... and you can still fail to 'get it'. So essentially, our reality is biased and as such... boy, it helps to see why we are supposed to forgive people almost everything. If the human mind can only create reality from what it has been exposed, then misunderstandings must be so easy. The mind will just pull out the bits of perception that it recognizes so that we can have understanding or comprehension- even though that probably will not give us understanding and comprehension. “ That which most closely relates to the unfamiliar from our past experiences, makes up what we see when we look at things that we don’t comprehend.”

So know that I truly understand this (at least I think I do.... :), what do I do? If I have communication problems based on the abuse in my past and the way that I was treated early in life, how do I change. What I mean is, I can change outward behavior and I have in many ways. I no longer have a 'anger' problem- I just have to be aware of my emotions an understand that I have a penchant towards anger. By knowing this, I am able to control it. But how do you truly control thought patterns that have been a part of you for so long that I am unable to even recognize that they are thought patterns? How does anyone do it? David Pelzer is an example that I can think of. He had some of the most horrendous abuse I have ever heard of or read about... and yet he has been able to change his actions and his thoughts (at least it appears that he has). Clearly this is a loooong process. So...

How does perception effect you and your relationships? How does it affect your communication with others? How does it affect how you do.... everything!? If you have had abuse in your past or other major problems such as divorce, instability, etc.... how have you dealt with it? What has worked to help change the way you think..... has it worked? Carlfred Broderick talked about a transitional character- one who is able to purify their family line from the blackness and instability of the past and give future generations the ability to not have to confront the pain and scarring. In the past I have thought that I have been pretty successful at being a good transitional character and I have the best husband for that- his patience and kindness are a Godsend that I do not deserve. But... I suspect I have a lot more work to do!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_by_English_School.jpg)